Too many crises. Climate has been pushed to third place, and the Coronavirus to 2nd, with the United States now embroiled in a cycle in which police violence leads to protests which are met with more police violence. I hope some of the other countries, the ones that have citizen-friendly policing and that have gotten their daily new Coronavirus case rates down into the low hundreds, are still working on climate while we Americans thrash around.

Thrashing around in the more immediate issues of the moment, while the climate slowly warms, has been standard operating procedure for the developed world ever since powerful people were first told about greenhouse gases, which for the American Petroleum Institute was 19591.

Since then, year after year, we’ve always had bigger fish to fry. The recent increase in climate awareness has not led to a corresponding increase in action, because it’s never just been about awareness. We’ve been aware of out-of-control policing2 in America for a very long time too, and yet it’s still here.

In this blog, I try to focus on the specific, the knowable, and the actionable. Gazing into the crystal ball to try and guess what our species is going to decide to do isn’t any of those things, and also tends to lead down dark paths, but that seems to fit the mood of the moment. So: Dave, what’s your plan? What’s your road map to lead the human race off the slope we’re sliding down into catastrophe?

Wow, I’m not that smart. I don’t have a plan. And I’m not the right person to come up with one, because I’m a nerd, messing around with technical ideas. While we would certainly need technical ideas in the course of getting off the disastrous slope, the main thing keeping us there now is a complicated set of “people problems.” All the clever technical ideas in the world are useless if we can’t aggressively put them into practice, and right now, we can’t; we aren’t. The reason we’re not acting vigorously against climate change, police violence, and the pandemic is because we don’t want to.

That’s shorthand, of course. Many of us do want to; a majority, in fact, if you take the simplistic view that every person has the same social power. The longer version is that enough of us have enough collective wealth, authority, cunning, and sociopathy—and enough others are duped by or afraid of those people—to ensure that things don’t really change, and that’s that. In the same way, Officer Derek Chauvin was outnumbered three-to-one by the rookie cops on the scene with him, men who had recently taken oaths to protect and serve the public3, yet they chose to assist him rather than stop him while he was murdering George Floyd (an outcome it’s hard to imagine any of those three would have wanted).

These things aren’t true in equal proportion everywhere, of course. There are many places in the world whose citizens don’t fear the police, have enjoyed a robust government response to the Coronavirus, and have even been able to compel their governments to start getting serious about climate.

Then there’s the U.S.—the nation where so many renewable energy ideas were born, where President Jimmy Carter put solar panels on the White House roof in 1979, 41 years ago—whose federal government (when not busy sowing racial suppression and authoritarianism) is doing its utmost every day to encourage even more fossil fuel use. Other large nations like Brazil are in similar hands. And sadly, greenhouse gases mix quickly into the atmosphere and are evenly distributed around the world, so New Zealanders are riding in the same toboggan as Texans.

That’s problem number one. In the short term, it’s politics. What has the votes to pass, and what doesn’t. Politicians, though, can’t stray too far from their power base, or they get booted out. So what really comes to pass is what the powerful people want, what the easily duped people are told they want, what the scared people will reluctantly accept, and what the oblivious people don’t know about. America could print trillions of dollars to fight the climate crisis, as we’ve done to fight wars or the Great Depression, but under current conditions, we won’t.

Now suppose we somehow get that boulder out of the road, and have a mandate to start writing fat checks for every big climate idea at once. On to the second boulder, which is that we no longer know how to undertake big projects, and execute them fast, under budget, and well. This amnesia has hit Americans especially hard, though there are plenty of countries where nothing big ever got done well. Corruption, vested interests, myths about capital, lawsuits, environmental impact studies, NIMBYism—too many root causes to unpack here, so I’ll save it for later.

But the record is clear. California is one of our most successful states in terms of putting political will behind renewable energy projects and getting them done. Let’s take a quick look at their experiment with high-speed rail: “There are so many obstacles to changing the status quo, and so many litigation opportunities at each stage, that we’re really looking at 20 years of consultants and lawyers and bureaucrats before these projects get started, and it’s almost impossible to maintain political and taxpayer support over that period,” said Jennifer Hernandez, a partner at Holland & Knight who leads the law firm’s West Coast environmental and land-use practice4.

The original budget estimate of $33 billion, for a system of “bullet trains whipping up and down the state, cutting a path from Los Angeles, through the orchards of the Central Valley and into downtown San Francisco5,” has ballooned to $77 billion, for a still-unbuilt system that would rather uselessly shuttle between Merced and Bakersfield.

A reader of the linked SF Chronicle article commented: “Small wonder that even in California we trail Europe and China and Japan in the development of efficient public transportation systems. This is reflected in the thousands of hours a commuter will spend sitting in traffic and the air pollution and high cost of housing in metro areas. This is the state that allowed GM, Firestone, and Standard Oil to rip out the trolley car lines without opposition. This is the state where county supervisors with a high school education could oppose and derail BART in the south bay. The state advisory board over Caltrans has members who represent the auto, construction, and real estate interests of the state while ignoring the costs to the public and to the environment. When freeways are built the land along them soars in value and this taxpayer subsidized windfall goes into the pockets of the developers and this is why the ridiculous route along the I-5 corridor to provide service to the cattle along the route and bypasses population centers in the state. We have regressed in transportation across the country and it takes longer now to go by train or by car to a destination than it did 50 years ago. We need to bring in the Chinese to show us how it should be done.”

If we get past those two obstacles, the third issue is identifying the best things to do to slow and reverse climate change. That’s where I have safely positioned myself, far from the front lines. I justify that by claiming that I’m no good at movement politics or building effective organizations; true enough. I also have a hunch that the willingness of common people to demand change could be favorably influenced by their being presented with a clear vision of how that change can be achieved, and proof that it can really work. I’m putting my little efforts into that pool.

If we get that far, we’ll encounter the same problem again: we need agreement among the powerful, with huge egos and vested interests everywhere. If the IPCC says we have 12 years6 to turn things around, should we go big on nuclear? (Classic, or Thorium?) Or wind and solar? These are false dichotomies, given that what we’re doing now is only and exactly what the unfettered crony capitalist free market wants to do, which is not very much at all. What we should be investing heavily in is everything. But without big changes to how we make those decisions, we can expect them to provide yet another opportunity for paralysis. (I’ve presented these boulders as if we’ll encounter them sequentially, but in fact we’re already well stuck behind each of them, all at the same time.)

So I don’t have a road map. I do have an observation about human nature, though. People don’t like change. They like a comfortable routine. And they aren’t very good at noticing that things have gradually been getting worse for years. Only severe, sudden pain and anguish will cause them to give up business as usual.

Here’s how I see things playing out. If science is even half right about climate, our future looks like an unpredictable series of disasters that will become more frequent and more catastrophic as time goes on. Fires, floods, droughts, crop failures, pandemics7, heat waves. More and more people will die in these disasters. Of the survivors, more and more will lose their jobs, their savings, their homes, everything they’ve worked for. Some of those who’ve lost someone or something important to them, whose comfortable routine is gone forever, will start to angrily demand change. The powerful, almost by definition, are better protected from these events than the rest of us, and so will be happy with the status quo for longer. (I remember that for a day or two, it looked like Hurricane Dorian might be planning to level Miami instead of the Bahamas—the consequences of that would have been interesting to say the least. But it’s early days.)

Many current leaders, concerned as always with maintaining their own positions, will look for scapegoats, or downplay the disasters. Meanwhile, new leaders will rise from the ranks of the fed-up and consolidate their angry voices. And new demagogues will pop up too, shouting who knows what.

As the years pass, each new worst-in-recorded-history disaster will change more minds, as it drops the hammer on people who were lucky up until then. If science is half right, it is 100% certain that at some point there will be no more climate deniers. The phrase will be an absurdity. We don’t talk about gravity deniers or oxygen deniers—we’d simply refer to such people as mental patients. And at that point, humankind will finally be united by one desire: getting a livable world back.

What happens then is going to depend partly on how fast things happen and in what order. Whatever our odds are now, in the spring of 2020, for reversing global warming while keeping the basics of civilization intact, those odds will get steadily worse each year. We could easily run out of time. If that happens, governments and legal systems will break down either into localized warring fiefdoms, or (if the necessary amount of oil can still be gathered for the project) into world wars. Either way, there won’t be enough food, water, medicine, or anything else to go around, and if history is a guide, each person, family, and sect will try to grab what they can from the others in a spiral of collapse.

On the other hand, if we are lucky with the timing and details of the early disasters, they will smack us hard enough to act as a wake-up call without crippling us in the process. There’s a Zen saying: “A good horse runs even at the shadow of the whip.” We’ll be getting much more than the shadow, but maybe, if smacked just right, another side of our nature will forcefully show itself. There are certainly people all over the world who have seen that shadow and have been warning us about it for years and years.

In this possible world, we will get our act together while we still have the resources and the level of social organization to effect meaningful change. Things will still get very bad, but some of the good parts of civilization will be saved. And there will be much less suffering.

What kind of resources and social organization? Most of us (who see the problem and haven’t given up) seem to be looking for a technology-based transition away from fossil fuels. Solar panels and wind turbines as meat and potatoes, some want to add nuclear to the mix, we all want more research into other possible side dishes like tidal energy or geothermal. Some type of electricity storage: lithium-ion batteries, flow batteries, pumped hydroelectric storage, hydrogen, compressed air.

Unfortunately, all of these are high-tech, and rely on a high-functioning, globally integrated economy. Many of them need uncommon materials that can only be mined in certain places in the world, so from the start we need global trade so people in other places can buy them and get them shipped.

The current economy works the same way for more ordinary materials like steel and glass, as well as for most manufacturing. These basics of modern life aren’t local any more—a complex product like a wind turbine could be made in many places in theory, but the way we do it now is to concentrate that expertise in a few places and ship the product all around the world. Just as it took decades to switch to this dependence on fragile global supply chains, just-in-time inventory and so on, it will take years (even on an emergency basis) to go back to the more resilient place we came from.

This is why, to have any chance at all of making this worldwide tech-based energy transition, we can’t waste more time. COVID-19 is a reminder that our globalized economy is fragile, and can be completely disrupted overnight8. Disruptions like that can have many causes (from wars, to trade wars, to revolutions, to recessions) and will make energy transition drastically harder, and before too long, impossible.

Another thing that will make saving ourselves harder is that, throughout history, insecurity and fear often fuel authoritarian movements and fascist regimes. These regimes are more concerned with staying in power from one day to the next than with long-term, wisely chosen projects for the common good. Americans may look somewhat enviously at China’s ability to build high-speed rail, hydroelectric dams, and transmission lines, but even the relatively pragmatic Chinese regime of the moment is the inheritor of Maoism, a brutally repressive era characterized by loony, anti-scientific fads in leadership, and tens of millions of unnecessary deaths9. China’s leaders may manage to keep a firm long-term grip on power while keeping their totalitarianism “progressive,” but history doesn’t make a strong argument for that.

I mentioned that there are two ways we might respond, once we’ve all figured out that lurching from one climate catastrophe to the next is the new normal. The key to that response will be empathy, a human trait that is currently at a very low ebb. That’s no accident, it seems to me; we’ve been breeding it out, by allowing the least empathetic people to keep more and more of the rewards of humanity’s collective effort, and giving less and less to the most empathetic10.

I’m not suggesting that empathy is a panacea or that with enough of it, the lion would lie down with the lamb and there would be no more conflict. What I am saying is that widespread empathy sets a certain bar for how human life can be, and in the absence of empathy, it’s possible to go way below that bar. A society of completely selfish individuals with no compunctions about cheating, lying or stealing to maximize their own status can be horrible for everyone. Even going back to the society we had in the ’70s would be a big improvement, and that wasn’t all that great. Unfortunately, stability tends to breed cooperation, and instability breeds selfishness; so it’s a long shot to hope for a massive outbreak of compassion right now, but we’ve never been here before. And we do know that catastrophic events sometimes bring out the best in people, at least for a while.

We find ourselves in an epic, multi-generational three-way race between (1) the brutal, selfish, short-sighted side of human nature; (2) the empathetic and cooperative side of that nature; and (3) the worsening environment, which will force each of us to show our cards. Only one of the three bodes well for civilization as we know it. I’ve started to think that if there are history books in the future, the chapter about these next few decades might be titled “The War For Earth.” We’re well into it already; all the trends are in motion. We truly live in interesting times, and our actions now will ring through many thousands of years to come11.

I have a vague forecast, then (with no guess as to the outcome), but not a plan. Do I have hope?

I’m not sure I do, but I’m also not sure how much that matters. Hope is a feeling; it would be nice to sit around feeling full of hope all day, but what would that change? I do know (and am glad) that I can’t begin to know what is going to happen. That’s because the world is so large, complex, multifaceted, and intertwined that my regular-sized brain is overwhelmed by it, and if that brain came to any big-picture conclusions as it yearns to do, I would know better than to trust them. I find uncertainty helpful. Uncertainty is cool and normal. It just wouldn’t feel right to give up when the field is hazy, reports scarce, but the battle might not yet be lost.

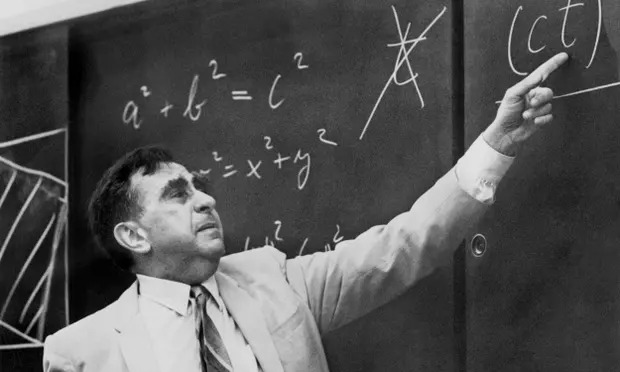

- On its 100th birthday in 1959, Edward Teller warned the oil industry about global warming (theguardian.com). Exxon had a very detailed understanding by 1977 (scientificamerican.com)

- “The Police Are Still Out of Control” – Frank Serpico, 2014

- The widely used oath embraced by the International Association of Chiefs of Police reads, “On my honor, I will never betray my badge, my integrity, my character or the public trust. I will always have the courage to hold myself and others accountable for our actions. I will always uphold the Constitution, my community, and the agency I serve.”

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/25/us/california-high-speed-rail.html

- https://www.sfchronicle.com/politics/article/Train-to-nowhere-Here-s-how-high-speed-project-13621347.php

- Now 11 years, going on 10. https://www.vox.com/2018/10/8/17948832/climate-change-global-warming-un-ipcc-report

- Halt destruction of nature or suffer even worse pandemics, say world’s top scientists (theguardian.com)

- IEA says the coronavirus crisis has set in motion the largest drop of global energy investment in history (cnbc.com). “In the group’s annual World Energy Investment report, published on Wednesday, the IEA said that the unparalleled decline in worldwide energy investment had been ‘staggering in both its scale and swiftness’.”

- “Local officials were fearful of Anti-Rightist Campaigns and competed to fulfill or over-fulfill quotas based on Mao’s exaggerated claims, collecting ‘surpluses’ that in fact did not exist and leaving farmers to starve.“

- Whether it’s plausible that this is literal breeding for traits, of the sort we do to dogs, depends on how far back you think it started. I would date it to when we began cultivating cereal grains, which were likely the first form of storable wealth, and made possible the invention of the rich person.

- “Close Calls: Three Times When Humanity Barely Escaped Extinction“; “How shellfish saved the human race“; “Abrupt Impacts of Climate Change“

Hope does spring eternal in the human breast (to mangle a quote), but hope by itself saves no-one. Each of us can do something NOW to help save the planet we live on. Make your home more energy efficient. Stop using plastic, really recycle, stop eating meat and dairy, compost, conserve water, buy hemp paper products instead of tree pulp, buy local produce and goods, use a bicycle when possible, etc.

Each of us has to contribute in order to feel a part of a potential solution, no matter how dire the problem seems to be. That’s hopefulness to me, not smugness or complacency, but just a tiny start.

Very good point.

If I had a friend who was addicted to heroin, I might say, “Your feelings and your reasoning are both kind of disordered right now, so you have to examine them and not just trust them.”

And we first-worlders are all raging addicts. We’re hooked on convenience, comfort, and immediate gratification because of our (temporary) mastery of Nature. We need some distrust of our feelings about things. We need to add a little discomfort and inconvenience back in, so we can gradually re-learn that they’re just part of life. Composting and saving water are a pain. We don’t want to have to care or think about them. But we need to start fixing our brains.

Excellent points. I’ve heard our current lifestyle described as “radical comfort.”

About discomfort: in a book(let) called “Principles of Ecological Design” by the greywater expert Art Ludwig, he asks, “Is it worth four times the cost, complexity, and resource use to have hot water 99% of the time instead of 90%?…bumping into the limits of system capacity provides useful feedback, which raises awareness and promotes good habits.”

It’s about having a more direct relationship with the earth, less swaddled, more vulnerable. Risking vulnerability tends to take you to a deeper and more satisfying place with a partner, or an art. Why not a planet?

We’re not ready yet. We’re still entranced by what we’ve done with the world.

It’s hard to give up being a god, even a fake one.